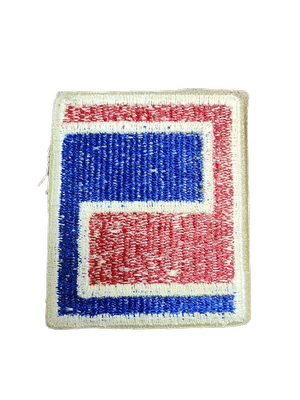

69th Infantry Division

From the moment the allies landed on the smoking beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, everyone knew what one of their principal objectives was—to slash deep into Germany itself and cut the Nazis’ defenses in two by joining hands with the Russian armies driving from the eastern front.

More than ten months later, on April 25, 1945, the dream came true.

A patrol of the 69th Division—the “Fighting Sixty-ninth” of this war—jumping from the Division’s positions on the Mulde River across the Elbe, climbed to the top of an old tower at Torgau, on the west bank of the Elbe, and saw some Russian soldiers across the river.

A few minutes later American and Russian hands were clasped halfway across a battered bridge that spanned the river, and official contact had been made between the two Allies.

There were other meetings with the Russians by other men of the Fighting Sixty-ninth, but Torgau was dubbed the “official” junction. The Division itself will probably never stop arguing as to which of its units first joined up with the Red Army— but no other division can dispute that honor with the 69th.

The “Fighting Sixty-ninth” first saw action on March 8, in the Siegfried Line, when two regiments crashed the fortified line on a 2,000-yard front. The Doughboys of the 69th took 200 prisoners on their first day in combat, and shortly captured Rescheid, Jamberg, Dickeerschied, and Honningen, among Dther towns. That was the official start of the battle for the 69th, but many weeks earlier, while the Division was waiting in France for its chance to show its stuff, four members of the 69th’s quartermaster company had made an unofficial start when, on a routine trip to Reims for supplies, they had bagged some Germans hiding out in a French farmhouse.

At the junction of the Moselle and Rhine Rivers, the 69th :ook the ancient fortress of Ehrenbreitstein, but their first important victory was at Leipzig. There, on April 19, the 69th, ilong with the 11th Armored Division, finally forced the surrender of fanatical German defenders who fought a last bloody itand at the base of Napoleon’s monument until they were blasted out by heavy fire from self-propelled guns.

There are many high points in the 69th’s combat chronicle— the capture intact of a 70-ton bridge across the Weser River, and the occupation of dozens of small German towns like Nissmitz and Fürstenwalde and Maidenbressen, for instance—but until something better comes along the Fighting Sixty-ninth, and the Russians who held the other side of the Elbe, will always put Torgau at the top of their list.

April 25 was really a red-letter day.

From Fighting Divisions, Kahn & McLemore, Infantry Journal Press, 1945-1946.